In popular media, Voodoo is often shown as a kind of “dark magic.” Some people even think Voodoo is naturally evil, partly because of things like Voodoo dolls, creepy-looking imagery, and rituals that are very different from those in Abrahamic religions.

But Voodoo (often spelled Vodou or Vodú) is not an evil religion. It focuses on a deep connection to the spiritual world. The spirits called upon in Vodou rituals, lwa, are somewhat like the Christian idea of saints. And despite the idea that Vodou is about Devil worship, the Devil doesn’t exist in most versions of Vodou belief.

In fact, some might be surprised to learn that Haitian Vodou is partly influenced by Christianity, blending traditional West African religions with Roman Catholic beliefs. As Vodou became important among enslaved people in what is now Haiti between the 16th and 19th centuries, a similar practice also found its way to the United States.

Enslaved people taken from West Africa to America in the early years of the nation’s founding also brought their traditional beliefs with them. Like in Haiti, West Africans in what is now Louisiana mixed their traditional religions with Roman Catholicism, which led to Louisiana Voodoo (also called New Orleans Voodoo). After a slave revolt in Haiti in 1791, many followers of Haitian Vodou fled to Louisiana, bringing their influence there too.

Though many have tried to stop Haitian Vodou, Louisiana Voodoo, and other West African diasporic religions, they still exist today, especially in the Caribbean and New Orleans. Thankfully, public opinion of Voodoo (or Vodou) has started to improve, even if it’s happening slowly.

The Fascinating Origins Of Haitian Vodou

As with many religions, it’s hard to pinpoint exactly when Haitian Vodou started. Most historians say it began in the 16th and 17th centuries when it became important among enslaved people in Haiti, and Roman Catholic missionaries partly Christianized it.

Vodou’s roots come from different traditional religions across West Africa. The word “Vodou” itself, in the Fon language of the African kingdom Dahomey (now Benin), means “spirit” or “deity.” When European colonists enslaved West African ethnic groups, they were forced to go to colonial Saint-Domingue (now Haiti), where Roman Catholic missionaries taught them about Catholicism.

The enslaved West Africans took these teachings and mixed them with their long-held beliefs, especially the West African Vodun religion. The result was Vodou, a belief that everything is spirit.

According to Vodou, humans are spirits who live in the visible world, but there are many other spirits beyond that. Lwa (spirits), mysté (mysteries), anvizib (the invisibles), and zanj (angels) all exist in an unseen spiritual world, along with the spirits of those who have passed away. This spiritual world is called Ginen, and Vodou practitioners believe that God — the same God worshipped by Christians — created this world and everything else.

This new religion became very important to many enslaved people from West Africa. As the University of Delaware reports, Vodou gave them a way to feel a sense of freedom, even in slavery, and helped them endure terrible hardships.

However, they had to practice their religion in secret because slaveholders had baptized them as Catholic and punished those who openly practiced Vodou. While the enslaved people did adopt some Catholic beliefs, they also secretly continued to follow their traditional beliefs.

Vodou Rituals, Spirits, And Worship

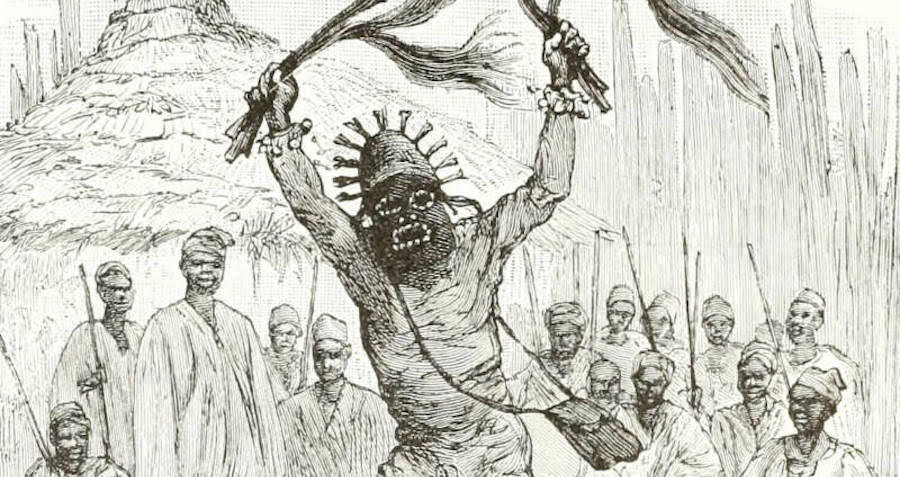

Unlike Christianity, Vodou doesn’t have a holy book like the Bible. It is mostly based on oral traditions, passed down through generations. Rituals include prayers, songs, dances, gestures, and sometimes animal sacrifices, all aimed at restoring the balance between people and spirits.

Some spirits called upon in Vodou rituals are ancestors or spirits of the dead, but there are other important spiritual figures — like Papa Legba and Baron Samedi — who can be summoned through specific rituals to communicate with them.

Vodou doesn’t have a central hierarchy, and practices can differ depending on the region. However, there are smaller local hierarchies that include manbo and oungan (priestesses and priests), ounsi (“children of the spirits”), and ountògi (ritual drummers) who form more formal congregations. Knowledge is passed down through the kanzo (initiation) ritual, where it’s believed that the human body goes through a deep spiritual transformation.

Like in Roman Catholicism, Vodou worshippers have a yearly calendar of ritual feasts, which usually match with celebrations on the Roman Catholic calendar. But instead of Christian saints, Vodou practitioners honor specific lwa spirits on these feast days.

This blending of Vodou and Christianity started in Haiti and later happened in Louisiana, where enslaved people also mixed traditional West African religions with Roman Catholicism, creating New Orleans Voodoo (or Louisiana Voodoo). The history of slavery is deeply connected to how Vodou (or Voodoo) developed, and while this is tragic, it shows how important enslavement was in shaping the religion.

How Slavery’s Brutality Led To The Growth Of The Vodou Religion

In the French colony of Saint-Domingue, Vodou first started to grow in what is now Haiti. Later, in the U.S., Voodoo further developed in Louisiana, another French-controlled area. During the slave trade, enslaved people were forced to work long, exhausting hours and were treated with extreme cruelty. Slaveholders often whipped and abused them and even tried to prevent people from the same ethnic groups from coming together, fearing they might unite.

Despite these hardships, many slaves found comfort in their shared suffering, and their connection to the religious practices from their homeland gave them a sense of security. This is why Vodou became so important to them.

As the Open Encyclopedia of Anthropology explains, “If the slave trade is a process of deportation that tore the individual away from his or her family, lineage, and clan, it is only to be expected that when a slave dies, every possible step must be taken in order to enable the restoration of links with the native land… The religious and cultural heritage of Africa was gradually restored through this semantic chain, which represented the link between the dead person and his or her ancestors and their divinities.”

Ironically, by trying to suppress African religious practices, white slaveholders ended up strengthening some slaves’ connection to these beliefs and rituals. These ties never fully disappeared, and this difficult period played a key role in shaping the Vodou (or Voodoo) we know today.

Unfortunately, many people still misunderstand Vodou, and it continues to be one of the world’s most misinterpreted religions. However, recent years have seen more people reclaiming Vodou in various communities.

How Modern Worshippers Are Reclaiming Vodou

Since the days of slavery in Saint-Domingue, people have tried to create fear around Vodou. This was originally done to encourage West Africans to convert to Catholicism and stop practicing religions like Vodou. Unfortunately, even today, some of these misconceptions remain.

For example, The Atlantic reports that a slaveholder named Médéric Louis Élie Moreau de Saint-Méry once wrote, “In a word, nothing is more dangerous, according to all the accounts, than this cult of Vaudoux. It is founded on the extravagant idea, which can be made into a terrible weapon, that the ministers of the said being know and can do anything.”

Some people still view Vodou as dangerous today, partly because of how “Voodoo dolls” are shown in pop culture. In horror movies and thrillers, these dolls are often seen as spiritual weapons used to harm others by simply poking them with needles. But in reality, these dolls aren’t common in Haitian Vodou or Louisiana Voodoo, and when they have been used, it’s usually for healing, not revenge.

Most Vodou practitioners say the religion isn’t “dark magic” or evil at all. Instead, it’s a way to connect with the spiritual world and has helped many people through tough times. As one worshipper, Alain Pierre-Louis, told The Atlantic, “Vodou is very big on respecting nature, remembering the ancestors, and the rhythm and vibration through dance, song, and the drum. Vodou is energy.”

Today, many refer to Vodou as the “national religion” of Haiti, though the Haitian government doesn’t officially say this. However, in 2003, Haiti did recognize Vodou as an official religion and allowed its communities to issue official documents. There is a popular saying that Haiti is “70 percent Catholic, 30 percent Protestant, and 100 percent Vodou.”

Vodou is a culturally important religion that survived brutal times, just like its followers. Every year, more people turn to Vodou, finding a welcoming and lively spiritual community.

As anthropologist Ira Lowenthal told The Guardian in 2015, Vodou reflects an unbreakable spirit of revolution.

“These people will never be conquered again,” Lowenthal said. “They will be exploited, they will be downtrodden, they will be impoverished — but you can tell not a single Haitian walks around with his head down.”